Don't miss any stories → Follow Tennis View

FollowNot the Only One | Parallels Between Djokovic and Azarenka

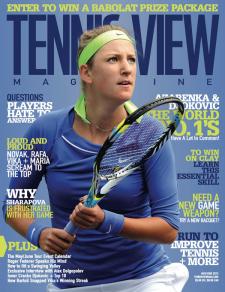

The conversation about the WTA in early 2012 had revolved around the rise of Petra Kvitova to the throne occupied by Caroline Wozniacki, an event awaited with little suspense. Abruptly redefining both of those conversations were the two players who snatched the momentum and the top ranking for themselves. We sketch eight parallels between the two No. 1’s that range from their playing styles to their personalities.

Better to Receive Than to Give (or Serve): While Novak Djokovic’s delivery does earn him free points, it still can fal- ter at key moments and does not rank among the most explo- sive in the ATP. Maintaining a high first-serve percentage at the expense of power, Victoria Azarenka can struggle with her second serve at times and rarely strikes unreturnable serves except on the fastest surface. On the other hand, both No. 1’s relentlessly subject their opponents to pressure dur- ing their own service games, perhaps to an unprecedented extent in the history of the sport. Not always aiming for out- right winners of the return, although they sometimes do, Djokovic and Azarenka have established an uncanny knack for placing their returns within inches of the baseline even on many first serves. Those shots thrust the opponent onto the back foot immediately, preventing them from starting the point in the offensive position that a server usually expects. The product of natural talent as well as evolving racket tech- nology, the scintillating returns of the top-ranked players may signal a trend in which breaks of serve become more frequent, leads less stable, and deficits less daunting.

Better to Receive Than to Give (or Serve): While Novak Djokovic’s delivery does earn him free points, it still can fal- ter at key moments and does not rank among the most explo- sive in the ATP. Maintaining a high first-serve percentage at the expense of power, Victoria Azarenka can struggle with her second serve at times and rarely strikes unreturnable serves except on the fastest surface. On the other hand, both No. 1’s relentlessly subject their opponents to pressure dur- ing their own service games, perhaps to an unprecedented extent in the history of the sport. Not always aiming for out- right winners of the return, although they sometimes do, Djokovic and Azarenka have established an uncanny knack for placing their returns within inches of the baseline even on many first serves. Those shots thrust the opponent onto the back foot immediately, preventing them from starting the point in the offensive position that a server usually expects. The product of natural talent as well as evolving racket tech- nology, the scintillating returns of the top-ranked players may signal a trend in which breaks of serve become more frequent, leads less stable, and deficits less daunting.

Two Hands Are Better Than One: With the notable exceptions of Djokovic and Murray, most of the ATP revolves around forehands rather than back- hands. Like the Scot, the Serb defied this trend by hitting his two-hander almost as a second forehand, generating similar pace and precision. The shot with which he first rose to fame, his backhand down the line remains his stead- iest weapon when the stakes tower highest and his most spectacular ground- stroke to watch. Azarenka similarly owes much of her ascent up the rankings to one of the smoothest backhands in the WTA, with which she can reverse directions seemingly at will. In contrast to Djokovic’s down-the-line rockets, her most vicious two-handers hook cross-court at vicious angles that stretch opponents out of position. To be sure, neither #1 struggles with their fore- hands, strokes that project ample power despite their lesser reliability. Both of them excel in taking that shot on the rise, and Djokovic in particular can hit all of its variants, from the down-the-line to the short cross-court angle to the inside-out to an inside-in especially useful on slow courts. But their brilliance in backhands suggests the importance of a symmetrical baseline attack in the modern game.

Tough Enough: Less than a year before her breakthrough at the Australian Open, Azarenka contemplated abandoning tennis in frustration over her inabil- ity to control her emotions. A host of assorted injuries also had plagued her throughout her career, causing observers to question her physical as well as mental stamina, such an essential attribute for a champion. Until late 2010, observers had raised similar concerns over the apparent brittleness of Djokovic’s willpower on grand stages as well as the apparent brittleness of his body. Beset by breathing problems and allergies, he had retired from three of the four majors, while Azarenka never played more than five consecutive tour- naments without a retirement or walkover in each of the last three seasons. In the months just preceding their rise to the top ranking, both #1s seemed to have solved or dramatically reduced these frailties. Djokovic has traced his sudden evolution into the ATP’s new standard of fitness to a gluten-free diet and a Davis Cup title, whereas the roots of Azarenka’s self-conquest look less clear. Of course, players like Zvonareva have claimed to have overcome the internal demons permanently when in fact they had suppressed them only temporarily, so perhaps we will not know for some time just how durable is the top-ranked woman’s transformation.

Angst, agony, and ecstasy: Overcoming a significant shoulder injury to claim the US Open title, Djokovic found a way to extract victories over elite opposition without his best physical form. One major later, he claimed another title despite showing signs of the negative body language that his critics had deplored during his underachieving years. For significant stretches of his victories over Ferrer and Murray, the world No. 1 played uninspired tennis unworthy of his talents, but his groundstrokes found the lines when absolutely necessary, and his confi- dence only mounted in adversity. To a lesser degree, Azarenka delivered her most resolute efforts of the Melbourne fortnight after some of her least convinc- ing stretches, whether the first-set tiebreak against Radwanska or the first two games of the final. When she injured her ankle in Doha, few would have faulted her for conceding her hopes of that title. The new No. 1 nevertheless steeled her- self to continue and not only finished off Agi Radwanska comfortably but routed the fifth-ranked Sam Stosur in the final. A year or two ago, Azarenka surely would not have mustered that resilience.

Master and Mistress of Ceremonies: Both No. 1’s know how to brand themselves on matches in critical ways. Audible from outside the stadium, Azarenka’s shrieks have generated a hurricane of debate over their origin, pur- pose, and validity. Before she reached the top ranking, in fact, many fans knew her less for her tennis than for her audible expressions of intent. But Azarenka certainly does not stand alone in that category, occupied by such exalted figures as the Williams sisters and Maria Sharapova in addition to Wimbledon champion Kvitova. Indifferent thus far to public perception, the WTA No. 1 has responded with defiance to this angle of criticism without yielding any more ground than she does on the court. Among the first impressions registered by viewers of a Djokovic match is its methodical pace, highlighted by his habits of repeated ball bounces before serves and leisurely strolls behind the baseline between points.

Neither of these No. 1’s must believe the conventional wisdom that momentum ends with the off-season, the brevity of which likely boosted their fortunes. In 2010, a then-wobbly Djokovic reached his first major final in nearly three years at the US Open. Competing courageously despite the ultimate loss, he then lifted Serbia to its first Davis Cup title and arrived at the next major with his confidence raised to unprecedented heights. Somewhat less stunning but similar in trajectory was Azarenka’s 2011-12 rise, which began by reaching the final of the year-end championships in the finest result of her career to date. Like Djokovic, she lost a fiercely contested match to her leading rival, but the impetus from that achieve- ment soared straight into the next year with three straight titles. Just as the Serb did not meet Nadal in Melbourne, neither did Azarenka meet Kvitova

Neither of these No. 1’s must believe the conventional wisdom that momentum ends with the off-season, the brevity of which likely boosted their fortunes. In 2010, a then-wobbly Djokovic reached his first major final in nearly three years at the US Open. Competing courageously despite the ultimate loss, he then lifted Serbia to its first Davis Cup title and arrived at the next major with his confidence raised to unprecedented heights. Somewhat less stunning but similar in trajectory was Azarenka’s 2011-12 rise, which began by reaching the final of the year-end championships in the finest result of her career to date. Like Djokovic, she lost a fiercely contested match to her leading rival, but the impetus from that achieve- ment soared straight into the next year with three straight titles. Just as the Serb did not meet Nadal in Melbourne, neither did Azarenka meet KvitovaThis article is from the May / June 2012 issue |

|

|

SOLD OUT Subscribe now and you'll never miss an issue!

|