Don't miss any stories → Follow Tennis View

FollowViewpoint: The Battle of Style and Substance

With tennis and soccer hosting their most important events simultaneously, there’s one conspicuous difference that’s been highlighted like never before: each sport’s appeal to the casual fan. With the Brazil World Cup usurping headlines in social media, Wimbledon in many places has been reduced to a mere footnote. The difference is easy to understand without necessarily comparing the popularity of the two sports. While a soccer game is overloaded with drama, infectious thrills, jubilant celebrations, and charismatic personalities, tennis is increasingly looked upon as a ball-punching baseline sport devoid of mercurial entertainers and sapped of uninhibited zest.

Not that that suggests that the likes of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic haven’t provided dazzling entertainment over the decades, or that they enjoy anything short of a legendary status on or off court. But it’s true that if tennis had to choose between two of sports’ greatest dichotomies, style and substance, the latter would win hands down. Pick any youngster whose future is making the tennis fraternity salivate, and the odds are that his or her game will seem like it has been put together by an Xbox engineer, cloning the near-perfect aspects from past or present champions.

“In tennis, the coaches want everything to be perfect. They want you to copy the others, but I’m not like that,” confesses Gael Monfils, one of the only players whose demise-of-funk-in-tennis memo probably got lost in the mail. With one Grand Slam semifinal appearance in the 10 years he’s been on ATP, ‘La Monf’s’ is largely considered a wasteful career among tennis purists, but his unbridled theatrics make him a crowd favorite.

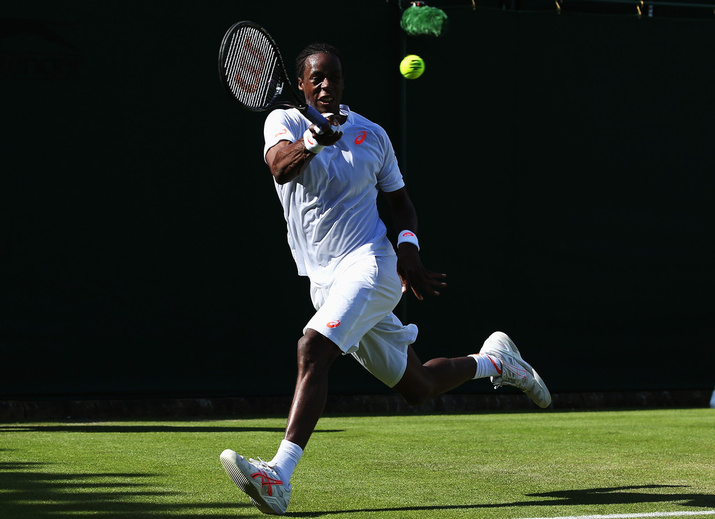

While most players run around the court, Monfils leaps, squats, splits, tumbles, slides, dives, and crashes, all the while retrieving balls and making improbable shots with his elastic limbs. “With adrenaline, I fly,” he admits. For proof, look no further than an image from Roland Garros last month where he went mind-bogglingly airborne and parallel to the ground at Phillipe Chatrier. Each time he’s on court, he’s just as likely to break out into a ‘Dougie’ dance as he is to hit a forehand like the hammer of Thor. When Monfils isn’t sleeping in his defensive camping tent a dozen feet behind the baseline or digging himself out of unnecessary holes he’s dug himself into, he’s unleashing cataclysmic blows at 100 mph. When he’s not shaking the crowd out of its stupor with his ridiculous court coverage, sliding and running like a panther set free, he’s pleading with them with his big innocent eyes and cheeky smile.

His unpredictability was once again the highlight of his second-round loss at Wimbledon, which encapsulated all that is captivating yet frustrating about the 6’4” French showman. Playing Jiri Vesely in the second round of Wimbledon, he decided to show up midway through the match, remove the invisible cloak he’d been wearing in the first two sets, turn the match on its head by running through the third and fourth sets, and then surrender tamely in the fifth. “My main thing is playing physically, and I can’t on grass. It’s not fun at all, for me,” he said later.

But does that stop him from showing off his ability to create the dramatic out of the ordinary? Not a chance. Down two sets to love, 4-4, 30-0 in the third, what should have been a simple backhand volley flick down the line turned into a backhand cross-court volley swat while simultaneously leaping and twirling several inches off the ground.

There’s another co-star who shares this unconventional tennis trick-or-treat style of play . This is the young Ukrainian Alexandr Dolgopolov, who fell to Grigor Dimitrov in an entertaining five-setter on Friday.

Nicknamed the ‘Dog’ (despite sporting a cat-that swallowed-the-canary grin), Dolgopolov’s short, unpredictable career is undergoing a renaissance of sorts with impressive wins over Nadal, David Ferrer, Milos Raonic, and Fabio Fognini this year. Currently ranked No. 22, he has an unprecedented style of play and spur-of the-moment shot selection. His talent promised much when he broke into the scene in 2011. Being described as “aggressive to the point of psychosis” by Andy Roddick, Dolgopolov has largely been an accessory to entertainment since then. He has been plagued sometimes by injury, sometimes by coach troubles, but mostly by his conceptual inability to play for a win.

As a youngster, Dolgopolov consciously chose to move away from a classic technique, choosing instead to play instinctively. “I try to play unpredictably and make my opponents uncomfortable,” he says. Today, he has it all in his whacky arsenal. Very little of it is textbook tennis and he’s probably never played the same shot twice. His serve, basically a normal serve set to fast forward with a no-pause motion, is nothing short of an exploding fire bullet, clocking 42 aces in the second round. Viciously angled, dipping forehands can be winners or a tease. Unpredictable backhands consistently find logic-defying angles. And of course the famous quick-sliced drop shot , arguably the best on tour, which he cuts while scrambling, squatting, stretching, jumping, or all at once, or like a boomerang. Add to that his hypersonic movement, ability to alter the rhythm of a point and groundstroke pace and be ostentatiously explosive or quirkily elfish at will, and you have a player that can stake claim to possessing the most unorthodox set of skills in the game today.

And yet, the wins are far and few between for both these non-conforming, body-contorting geniuses. Interestingly, it’s not what the opponents do right, but what they do wrong. For every impossible winner, there are multiple unforced errors. For every sidespin forehand chop, there’s a basic textbook volley hit wide. For every swatted grazing-the-line forehand, there’s a multiplied number of misfired forehands into the net, into the crowd, and eventually out of the match. And then there’s collateral damage of defying the physical limitations their style of play inflicts on their bodies, leading to consistent injuries.

Time, one would think, would aid their quest towards arriving at that point where talent and expectations meet, but not with these two. If anything, it seems to be pushing them further away into the land of absurd. It’s possible that they’ll never make the jump from ‘promising potential’ to the ‘consistent last 8’ category. And what’s worse is that if they do, it’ll probably be at the cost of this eccentric identity that makes them special.

“Definitely I can win, I'm sure, because at one stage everything is going to come together,” says Monfils about his chances of winning a Grand Slam. One can only hope it’s without dampening the fireworks. Even if he doesn’t, maybe it’s time we accept that not all players are meant to be Grand Slam winners or make it to the Hall of Fame or have signature watches and luxury clothing lines. Some athletes are just meant to stretch the boundaries of what a sport should be and do that one thing just as important as winning – entertain.