Tennis Statistics: An Objective Analysis

This year’s Australian Open proved to be an exciting affair despite some notable absences on both the men and women’s side (Nishikori, Murray, Serena) and some surprisingly early exits from usually formidable players such as Maria Sharapova, Novak Djokovic, Garbine Muguruza and Stanislas Wawrinka. However, it could be argued that the most compelling match of the tournament came in the form of the women’s singles final between Romania’s Simona Halep and Denmark’s Caroline Wozniacki. With both players having already achieved a career-high ranking of world number 1, each was eager to capture their maiden grand slam in order to cement their names into the game’s history books.

With both television pundits and ‘so-called’ experts labeling Wozniacki and Halep as two of the game’s best movers, most consistent hitters and defensively minded players on the WTA tour it was only natural to expect an enthralling battle that would test both competitors experience, conditioning, and mental toughness; They did not disappoint. On the surface, it appeared that Wozniacki’s ability to win the majority of the longer points and extended exchanges was the key component to her victory, but if we turn our attention to some of the pivotal match statistics we may be surprised to learn how much our eyes can deceive us. With statistics and relevant data points readily accessible we are now able to deconstruct and interpret facts in such a way, that both players and coaches alike can tailor specific training protocols based on what actually happens on the match court rather than what we think happens. Sometimes faulty belief systems, resistance to change, and stubbornness can prevent the developmental process from reaching fruition and so using objective data while tossing aside opinion will only improve coaching techniques, training methodologies, and player performance.

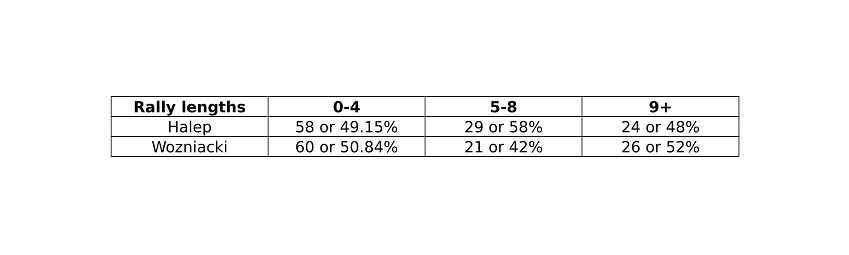

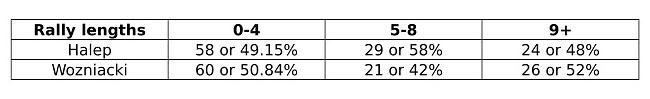

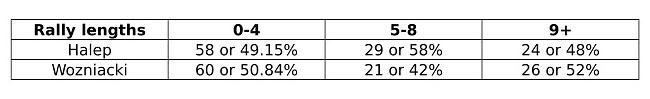

So what exactly separated these 2 great players in the final? Why did Wozniacki win and where was she better? With a total of 218 points being played, Wozniacki was able to capture a total of 110 of them while Halep was victorious in 108. With such a narrow point differential most people will jump to the predictable conclusion that the women’s final was decided by the long arduous rallies, laborious crosscourt exchanges and a style of tennis that relied heavily on surviving the war of attrition. They weren’t wrong. Well, not in the full sense of the word. The longest exchange in the first set was 19 shots while the third set saw rallies peaking at a staggering 23, allowing both players the opportunity to display their full range of physical capabilities and shot making ability. But, here is where things get interesting. The average rally length per point for the entire match (all 218 points played) was 5.31 shots, or put more simply, 2.65 shots per player. Essentially the match was about serve +1 and return +1 (first exchange). Furthermore, of all 218 points played, over 54% of them were decided within the first 4 shots, 22.93% of them between 5-8 shots and 22.93% of them lasting over 9 shots.

As most of you will have already figured out, the 2 point difference that occurred during this particular final resulted in Wozniacki winning a total of 50.45% of the total points, meaning 49.55% of the time she was losing. Throughout the entire tournament, Wozniacki played a total of 1024 points winning 569 of them, or 55.6%. In tennis terms that is a huge number; but doesn’t the average college, junior or recreational player expect to win almost every point? From a statistical perspective and contrary to most players beliefs that they need to win almost every point of a match to ensure victory, simply winning 55% of the total points will be more than adequate to ensure a 6-3, 6-3 win whereas winning 70% of the points would result in a 6-0, 6-0 victory (Brain Game Tennis) meaning that even in such a one-sided match the winner could still be losing as much as 30% of the total points played. All points are worth one but it would appear that some are worth more.

Despite all 3 sets being fiercely competitive, it is also worthwhile noting that while Halep was dominant in all 3 sets for the 5-8 shot category (58% match total) it was Wozniacki who held the advantage in all 3 sets for the 0-4 shot category winning a match total of 50.84%. The 9+ category had a total of 50 occurrences with Halep winning 24 out of a possible 50 (48%) while Wozniacki once again held a slight advantage winning 26 out of a possible 50 (52%). However, we must remain cognizant of the fact that the 9+ category had only 50 total occurrences throughout the entire match whereas the 0-4 category had an astounding 118 total occurrences. Where would you rather be more successful? In something that occurs only 22.93% of the time or something that occurs over 54% of the time?

Consider the case of Rafael Nadal who has dominated the French open throughout his career. Where is his strength? Longer or shorter points? According to Craig O’Shannessy (http://www. BrainGameTennis.com), despite most people’s beliefs that he dominates longer points Nadal’s real success comes primarily from the 0-4 shot exchanges and not as we may be inclined to think in the 9+ shot category. Seemingly it appears that when 2 players faceoff who are of similar ability then there is little advantage to be had in the 9+ category because by this stage of a point the advantage that the server initially held is all but lost. Although each point is ultimately judged by its ending (possibly why practice courts are ubiquitous with the site of players and coaches working on the longer points and finishing shots) it is ultimately the beginning phases of a point that will determine the way the point is played and finished. Consider it similar to a 100m sprinter. The winner of such a race is determined exclusively by who is first to cross the finish line but with all other factors being ceteris paribus a successful sprinter must be a master of successful starts. Current 100, and 200m World record holder Usain Bolt explains how important the start of his races are. “That’s where it all begins, if you don’t get a good start, it’s a lot tougher to relax and run your own race from that point on”. Maybe tennis can learn something from this thought?

So what does all this mean for you? Simply training players to work only on first exchanges and keeping points short is not necessarily the only solution but does provide us with somewhat of a ‘double-edged sword’. During most players matches points may often last less than 4 shots but it is largely because of unforced errors and double faults rather than winners of forced errors. To put it more simply the points are short because more bad things are happening than good! Tennis is a game of winners and errors and finding the right balance is often what separates the good players from the great. In order to understand this concept more, we need to evaluate something called the ‘aggressive margin’ which takes in to account how each point ends. When a point ends with a winner or forced error a +1 score is added to that players ‘account’ whereas if that same player commits an unforced error or double fault that player subtracts 1 point from their ‘aggressive margin’ score. For instance, if Wozniacki were to hit a winner, followed by a forced error she would have an aggressive margin of +2, but if she then proceeded to commit a double fault her ‘aggressive margin’ score would drop down to +1. This simple system provides us with a way of determining the overall quality of the points played and not just an arbitrary record of point lengths.

So how did the aggressive margin of both players look at this year’s Australian Open final? Of the 218 points played in this particular final, 146 (66.97%) of them ended with a winner or forced error (a +1 in the aggressive margin) and on 72 (33.02%) occasions points ended with an unforced error or double fault (a -1 on the aggressive margin). So for each player that meant a positive aggressive margin of +37 (146-72 divided by 2). This statistic is arguably the most important and provides us with the most pertinent information about what is actually happening during the points. As many coaches and players can attest to, it is not uncommon to be involved in or observe matches where both players ‘aggressive margin’ is close to zero or even in the negative.

What can we learn from this information and what is the take-home message? Whether you are a coach or player the primary consideration, and most commonly overlooked one is goal setting. Before a productive training session can be created the goals of all parties involved must be clear. Many recreational players use the tennis court as an alternative option to the gym, simply as a way to burn calories, improve physical well-being, socialize with friends and meet new people. For players like this, practices that are high in repetition, energetic and non-match specific (i. e. consistency-based hitting focusing on the 9+ shot category) are not only effective but recommended. On the contrary aspiring professionals, transitional juniors, collegiate players and competitive recreational players who are firmly invested in improving not just how they hit the ball but how they ‘play the game’ require an entirely different perspective with regards to their training approach.

Ultimately a points success will always be determined by the final shot that occurs but where the focus really needs to be, and where it is currently neglected is in the beginning phases. Perhaps the most under-trained shot in tennis is the return of serve, with the serve itself coming in a close second. Practice courts all over the world are abundant with players training 2 cross-court 1 down the line patterns, side to side basket feeding for 20 balls and co-operative rallying for 100 shots in a row. This is NOT wrong but its ‘weight’ on the practice court is extremely disproportionate with regards to what is actually required on the match court.

It is the responsibility of each player and their coach to set goals. Craig O’Shannessy (Brain Game Tennis) has proven through statistical analysis that throughout the professional ranks and all the way down through junior and collegiate levels that 0-4 shot exchanges occur approx.70% of the time (slightly lower at collegiate levels), 5-8 shot exchanges occur approx. 20% of the time and 9+ exchanges occur approx. 10% of the time. During this year’s Australian Open women’s final and despite two so-called ‘grinders’ taking center stage, the 0-4 shot category still occurred significantly more than any other category (5-8 and 9+). With this information now available we ought to reconsider our practice habits. Stop leaving serves until the last 10-15 minutes of the lesson. Avoid arbitrary repetition that lacks relevance and match application. Focus on serve+1 and return+1 patterns and avoid the temptation to focus on how you hit the ball rather than how you play the game. Based on a 2-hour practice and the aforementioned statistics, a typical training session should have its time allotment attributed as follows;

70% or 84 minutes= Serve+1 and return+1 practice with limited shot total point play

20% or 24 minutes= Baseline pattern play and movement and transition/Net play

10% or 12 minutes=Extended pattern play and movement.

(Above is a very basic outline)

For right or for wrong, I am a huge advocate of repetition and numerous studies have supported its importance and necessity when attempting to achieve professional status in any domain. Consider track workouts as an example of something that is used by tennis players all over the world as a way to improve physical conditioning and mental toughness, yet with regards to tennis specificity, its relevance is somewhat close to zero. No changes of direction, incorrect energy system utilization and maximal speed achievements (that do not occur on the tennis court). With this being said workouts of this kind can certainly provide us with some mental and physical benefits, but the problem would be if we were to employ only this training protocol and use it all the time. But isn’t this what we do on the tennis court year-round? Always focusing on consistency, extended rallies, no mistakes. I will repeat again to be clear. This year’s Australian open was contested between 2 players who are arguably the most consistent, defensively minded and formidable movers on tour. The average number of shots each player ‘hit’ per point was 2.65 and over 54% of the points were completed in under 4 shots.

The most difficult aspect of the information presented in this article for many players and coaches (including myself) to digest is it is somewhat contrary to what we teach or practice on a ‘day to day’ basis. It ‘screws’ with our entire belief system and coaching methodology effectively making us question everything we do. As players, it casts doubt over our training philosophies and creates an internal struggle between wanting to continue what we know to be comfortable versus embracing new that we need. The real question now is are we willing and able to make training adjustments or will our ‘egos’, refusal to adjust, or our indifference ensures that we continue to put more belief in what we think we need and happens, over what is really required and actually happens. On the surface, our lack of clarity on the practice court could be likened to a student preparing for a history exam but spends the majority of their preparation time studying algebra. Either way, the new statistical data that is available to us in the 21st century certainly provides some interesting food for thought. There is no single entity to blame for the current culture, but with no obvious panacea currently presenting itself, it is unlikely to change anytime soon unless some drastic changes are made.

A detailed breakdown of each point from this year’s women’s Australian Open final including point length, aggressive margin, winning percentage, and average shot count can all be found at http://www. FirstStrikeTennis.us. A PTR Professional, USPTA Elite Professional, and NSCA-CSCS certified strength and conditioning coach Mark has worked with players, such as Martina Hingis, Nadia Petrova, and Bethanie Mattek-Sands. Former Head Female Development Coach for the Kazakhstan Tennis Federation, Mark was the Director of Professional Women at International Tennis Academy in Delray Beach, Florida and is currently working for the professional ‘Star River’ Team in Guangzhou, China. Mark played Division 1 college tennis for the University of South Alabama and earned a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. Mark welcomes you to visit his website -www. firststriketennis.us where you can get more detailed statistics on the Australian Open final.